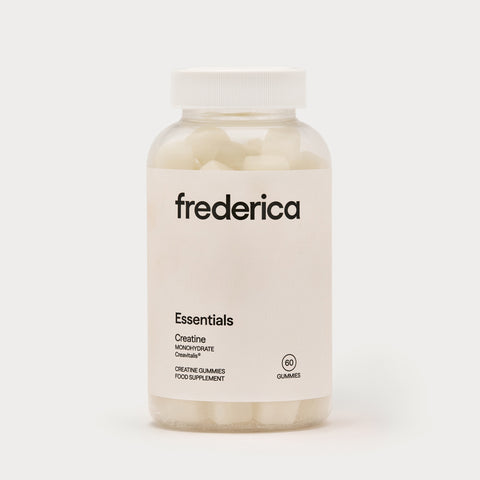

Uma gama de produtos para cada fase da sua vida

Na Frederica, unimos ciência, eficácia e prazer para a sua melhor versão.

As nossas fórmulas são testadas e aprovadas, seguem padrões de qualidade elevados e entregam resultados reais e consistentes quando integradas no seu ritual diário de bem-estar.

Acreditamos que a saúde é um compromisso diário com o corpo e a mente. Uma dedicação constante a viver com propósito e a crescer em direção à nossa melhor versão.

Pensada Para Si

Junte-se a uma comunidade que vive o bem-estar como um estilo de vida. Aqui, partilha-se uma saudável obsessão por crescer, cuidar e inspirar. Com acesso a eventos exclusivos, experiências pensadas ao detalhe e benefícios em parceiros que refletem o lifestyle Frederica. Um espaço onde milhares de pessoas caminham, todos os dias, na mesma direção: a sua melhor versão.