[April 10, 2016; Wilberforce Weekend, Arllington, VA]

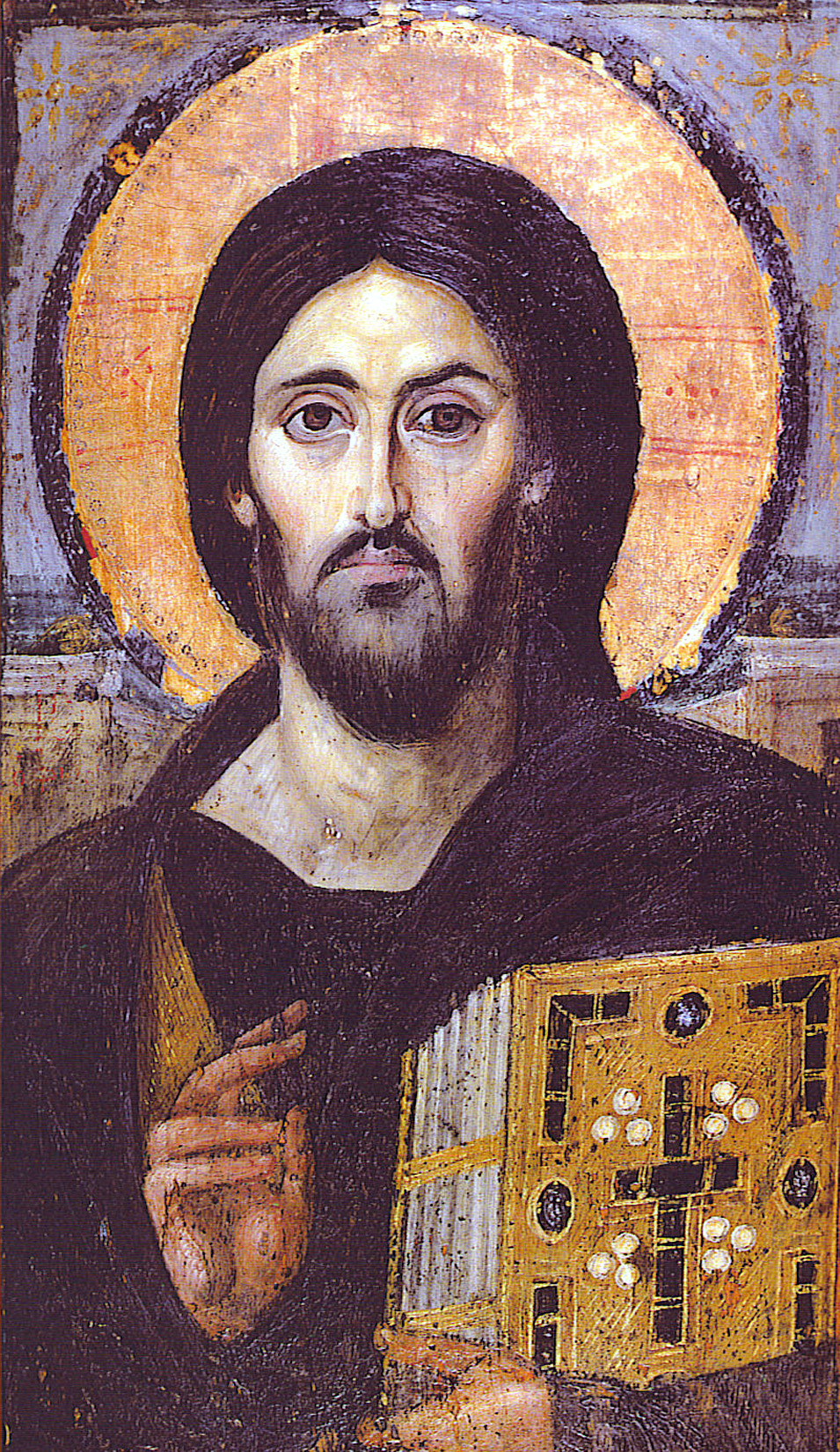

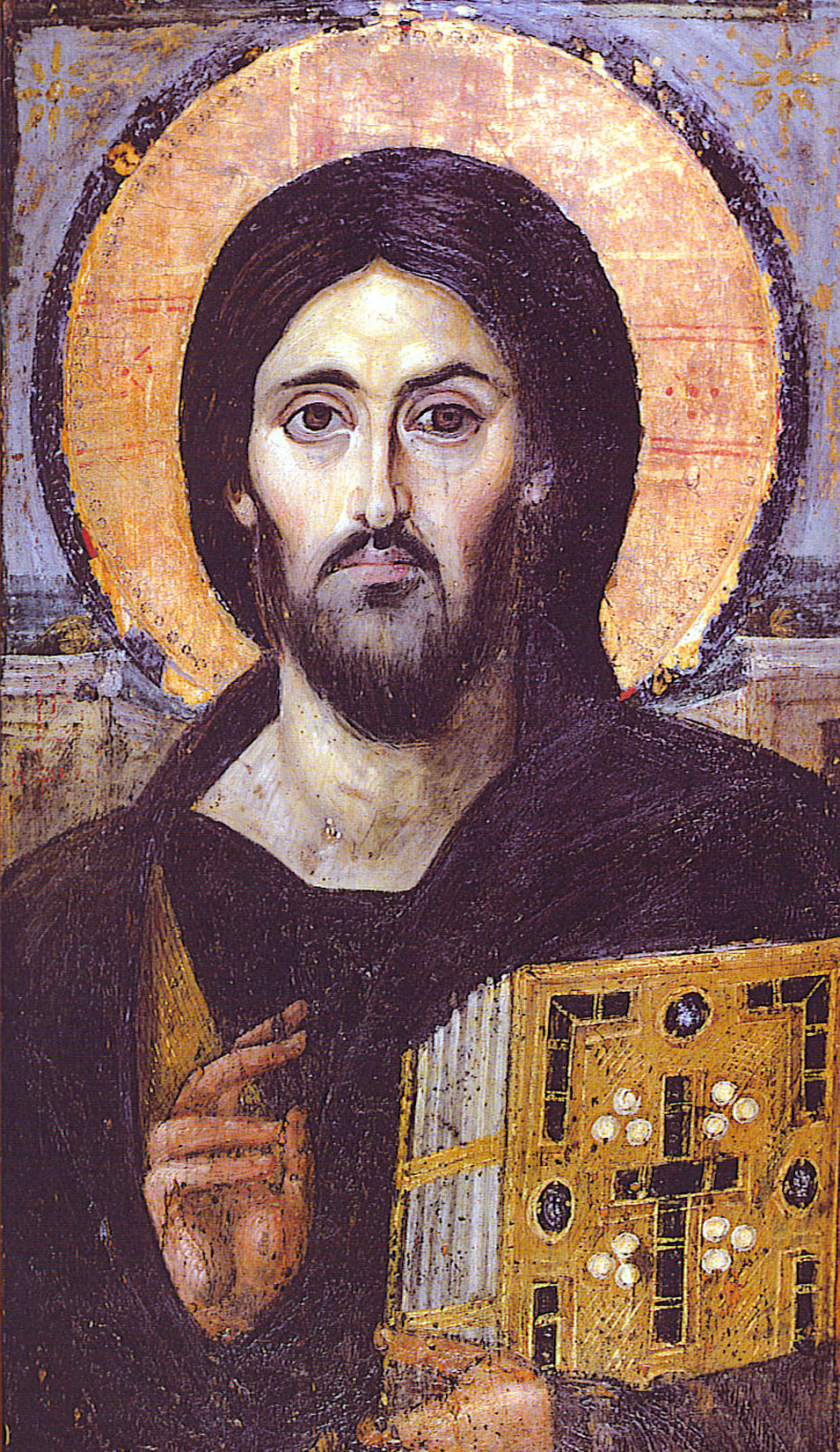

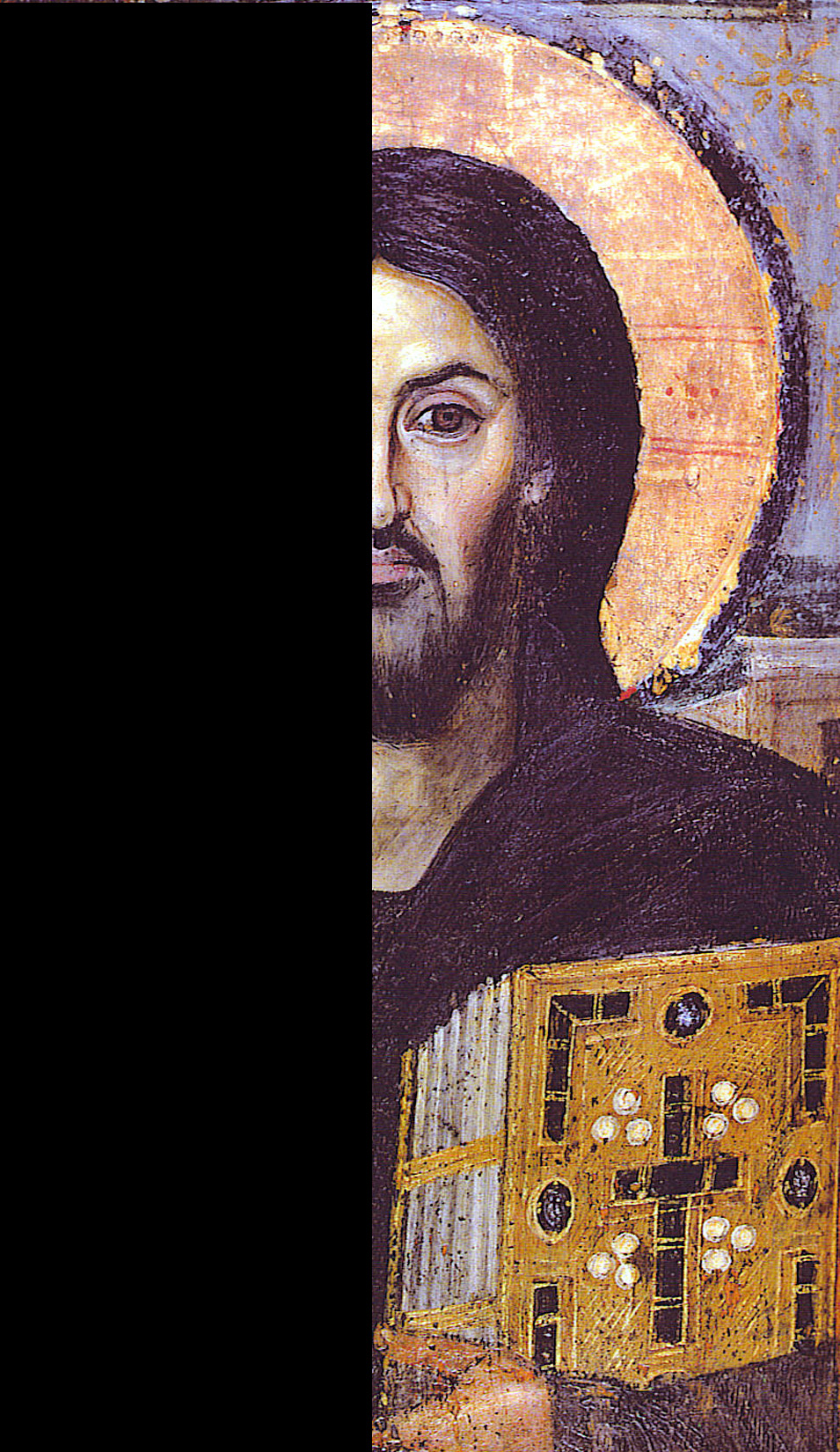

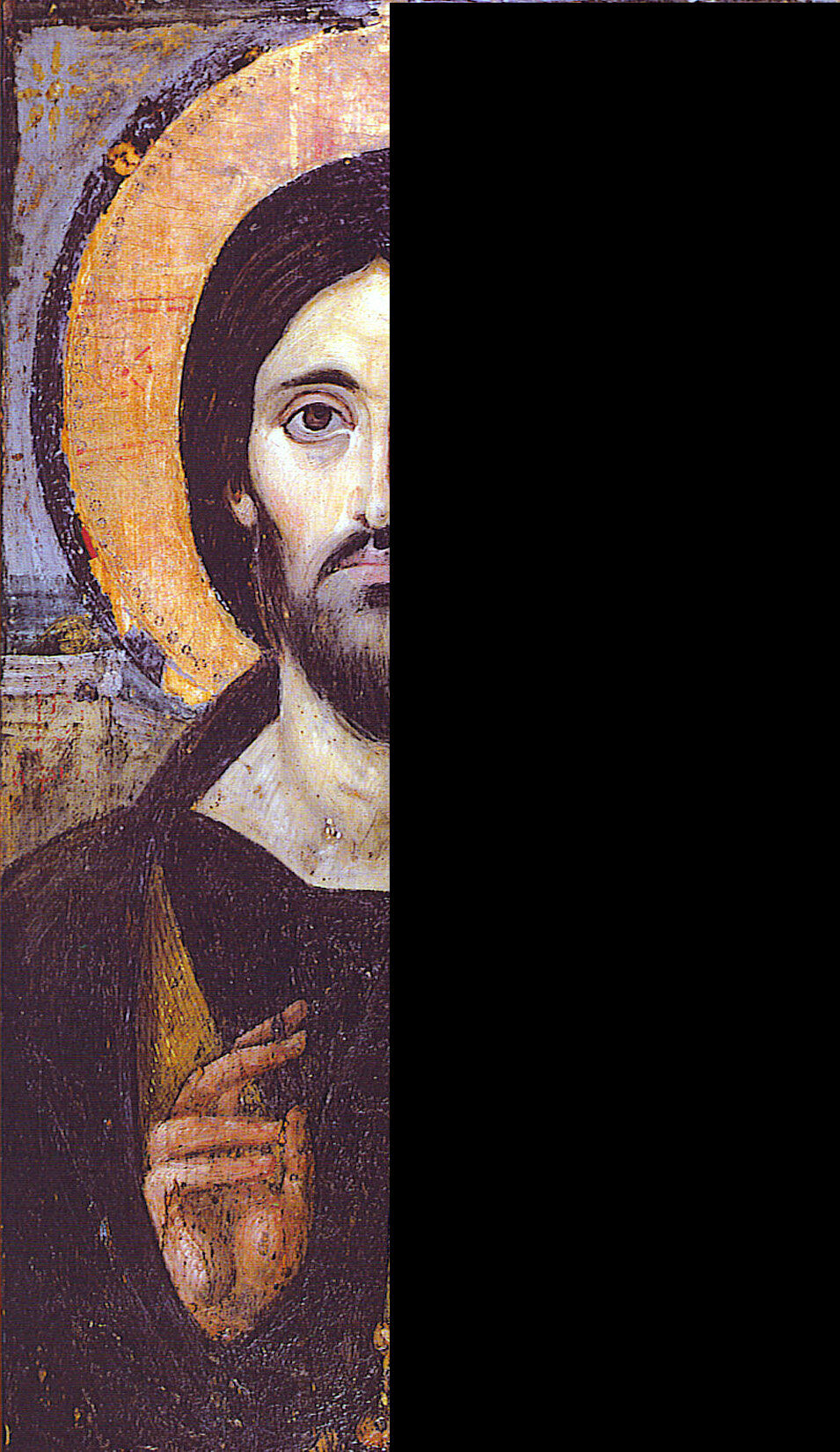

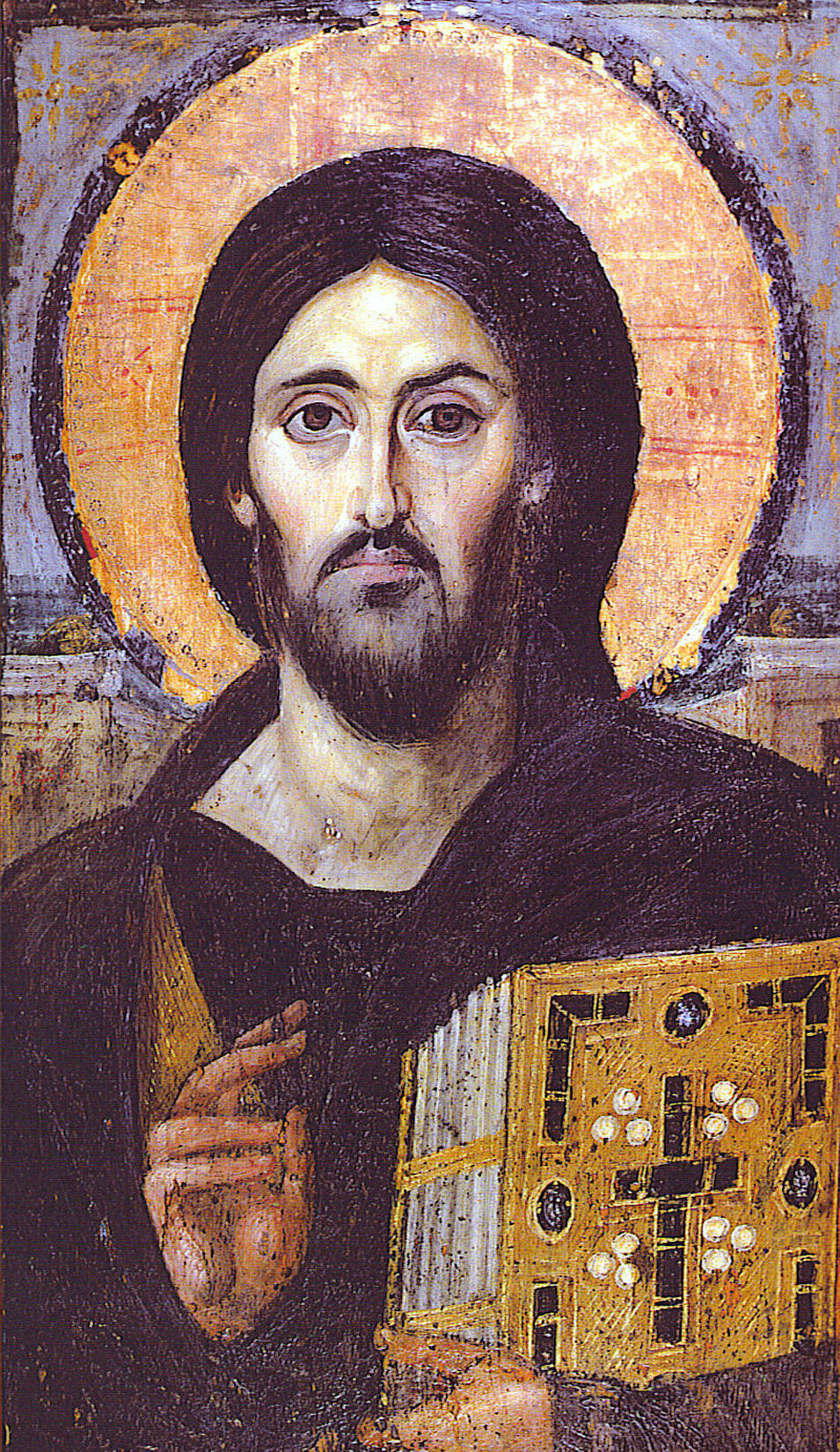

This icon is called the “Christ of Sinai,” and it was painted about 550 AD. It’s been in the monastery on Mt Sinai ever since it was built, 1500 years ago. –There’s a meaning to the penetrating quality of Christ’s gaze, which we’ll get to later.

In this session we’ll be hearing a lot about persecution, and I was asked to lead off by talking about repentance—which might sound irrelevant. Don’t we have enough to worry about already?

In this session we’ll be hearing a lot about persecution, and I was asked to lead off by talking about repentance—which might sound irrelevant. Don’t we have enough to worry about already?

But the connection is this. If our faith is going to be increasingly mocked and rejected, it will negatively affect our ability to speak in the public square. What we say will be distorted or ridiculed. Communication will be difficult. So we’ll need to put more emphasis on connecting one to one, person to person. Not just learning how to talk cleverly about our faith, but actually living it in ways that other people can see. The early Christians did this during the Roman persecution; they lived in ways different from their neighbors, and the church grew. Like them, we’re going to need to let the light of Christ within us shine out.

At present, American Christians are not notably shiny. Our lives don’t look much different from those of the world. Well, it hardly seems worth it to try. Since everyone is forbidden to have an opinion about anyone else, why bother with anything morally challenging? Advertising catechizes us, 24 hours a day, to prioritize comfort and amusement, and coaxes us to see our failings as excusable little foibles, that we ought to indulge. In accepting those views, we’ve gotten out of step with our fellow Christians throughout time.

In talking about repentance you have to talk about sin, and I wanted to recommend an understanding that is a little different, from my Eastern Orthodox tradition. We don’t see sin as being like breaking a rule. It’s more organic than that, and more communal. Sin is sickness. Though we’re born innocent, but we have a genetic weakness, so to speak, and catch the infection in time. And as we grow we add our own sins to the world’s store of misery.

So sin is infection, not infraction. It’s like air pollution: it’s something that we all contribute to, and we all suffer from. That’s why resisting sin is important. That’s why it has urgency. Our sins poison us and those we love, and add to the dysfunction of the world. But it is possible to resist. With practice, you can gain victory over one sin after another. This is a lifelong process, but the results are increasingly visible as time goes by. Like physical therapy, it’s a challenge, and sometimes it’s painful—but it keeps making you stronger.

Our life on earth has a goal; we’re not just waiting around to go to heaven. We were created to be filled with the presence of God—like the Burning Bush was filled with fire, like Christ on the Mount of Transfiguration was filled with light.

But because we are damaged and darkened by sin, we don’t shine that light very clearly. We are like lumps of coal, of no particular beauty. But coal can do one thing: it can burn. God created us able to bear his fiery presence. Repentance is the process of getting the impurities out of the coal, getting rid of everything that will not burn.

So that’s our starting point. Repentance is not self-hatred; it’s not an emotion at all. Repentance is just honesty—facing the truth about yourself, and meeting the challenge to change. I like to say “Everybody wants to be transformed, but nobody wants to change.” Transformation sounds lovely, and there are forms of spirituality that feed on narcissism. But this approach requires honesty, humility, and hard work—and it shows visible results.

The Greek word for repentance is metanoia, which is a compound: the prefix meta, and nous, which is usually translated “mind.” St. Paul says “We have the nous of Christ” (1 Corinthians 2:16). But the nous was damaged in the Fall, like everything else. It doesn’t work very well, it’s not accurate. It needs to be healed. “Meta-morphosis” is the transformation of the morphe, the shape; “meta-noia” is the transformation of the nous, the mind.

This is a lifelong process of healing, and God is like a surgeon. He knows what’s wrong with us much better than we do. He understands us better. He knows exactly needs to be done, to restore us to his image and likeness. God is the surgeon, and our job is just to get up on the operating table.

We do that by being faithful. We keep practicing the “workout routines” Scripture teaches: private prayer and bible study, corporate worship, fasting, care of the poor. One of the insights of Eastern Christianity is that sin starts with a thought (James 1:14-15). Sin begins with a thought, and habits like the ancient Jesus Prayer teach us how to recognize an unwanted thought—whether of pleasure or despair or fear—and turn it away. You don’t fight it—that can just backfire. But, standing beside the Lord at the entrance of your mind, you can recognize a thought and turn it away. So metanoia, transformation of your nous. St. Paul said, “Be transformed by the renewal of your nous” (Romans 12:2).

This is a complex therapeutic process, and it is going to happen in the order God knows best—which might not be the order we expect. Sins form an interlocking structure within our frail and foolish selves, and that framework has to be dismantled in the right order. A sin we especially want to get rid of might be held in place by a different sin, one that has to be removed first, even though we might not get the connection.

The process is like carefully removing the layers of an onion. You have to deal with the next layer that presents itself, even if you’d prefer to jump ahead. Jesus knows what we’re strong enough to bear at what point. He said, “I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now” (John 16:12).

St. Paul said we should be like an athlete striving for the prize, (1 Corinthians 9:24), and if you stick faithfully to your exercise routine, you will be amazed at what God can do with you—and in such a natural way that each step feels quite obvious, and never more than you can bear. God is the doctor and we are the patient, but we have a choice about whether we are going to be a cooperative patient. You have to show up, and you have to get on the operating table.

But what does that have to do with times of persecution?

This is called the Palatine Graffito; it was scratched on a wall at the boarding school for imperial page boys, on the Palatine hill in Rome, about the year 200. It’s the earliest depiction of the Crucifixion ever found. The writing says, “Alexamenos worships his god,” and, as you see, the crucified Christ has a donkey head. A Christian boy was being ridiculed by his classmate. This is the earliest depiction of the Crucifixion, and it ridicules the Cross.

This is called the Palatine Graffito; it was scratched on a wall at the boarding school for imperial page boys, on the Palatine hill in Rome, about the year 200. It’s the earliest depiction of the Crucifixion ever found. The writing says, “Alexamenos worships his god,” and, as you see, the crucified Christ has a donkey head. A Christian boy was being ridiculed by his classmate. This is the earliest depiction of the Crucifixion, and it ridicules the Cross.

Being faithful in repentance will definitely change you. But the changes might not be ones that make you more popular. What does our age admire? Well, what’s on the movie marquee? Vengefulness, sarcasm, potty humor, sex and greed. Christ will instead make you more humble, less clever, more simple. He will make you more like himself. And the world does not always love Christ.

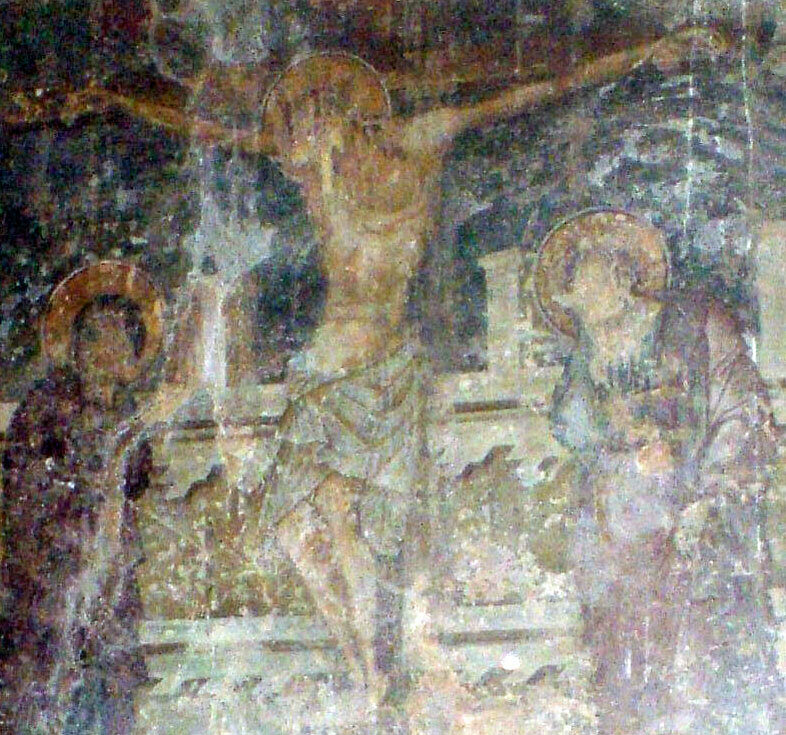

This is a defaced icon in a church in Goreme, in modern-day Turkey. It was painted in the 11th century. When invaders took over Cappadocia, when they came across Christian art, they scratched out the eyes.

“If the world hates you, know that it has hated me before it hated you. If you were of the world, the world would love its own; but because you are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world, therefore the world hates you” (John 15:18–19).

Another one, from Colossi in Greece, 15th century.

Another one, from Colossi in Greece, 15th century.

We can read in history and in the daily news that persecution of Christians can reach bloody extremes. We don’t know what God will ask us to bear. Perhaps only mockery, contempt, and financial loss, and not physical danger. “You have not yet resisted to the point of shedding blood,” says Hebrews 12:4.

But anything is possible. They crucified our Lord, and then they mocked those who worshiped a crucified God.

Goreme in Turkey, 10th century.

Goreme in Turkey, 10th century.

Even his image enraged them; even on the image that reveals the height of Christ’s love, they scratched out his eyes.

And yet we must love them as much as he did. And some of them will love him, too.

When I first saw the Christ of Sinai, I thought, “There’s something wrong with the eyes.” Then I realized that, what the artist has done here, is depict two different facial expressions side by side.

When I first saw the Christ of Sinai, I thought, “There’s something wrong with the eyes.” Then I realized that, what the artist has done here, is depict two different facial expressions side by side.

This right side is the eye of the surgeon; it’s a diagnostic, searching eye. It’s not comfortable under this gaze. But there’s actually a bit of humor in it—in the crook of the eyebrow, and the little lift at the corner of the mouth. This is an expression that says, “Oh, I’ve got your number.” This is the eye that looks right through you, right through your darkness, and wills to fill it with light.

This right side is the eye of the surgeon; it’s a diagnostic, searching eye. It’s not comfortable under this gaze. But there’s actually a bit of humor in it—in the crook of the eyebrow, and the little lift at the corner of the mouth. This is an expression that says, “Oh, I’ve got your number.” This is the eye that looks right through you, right through your darkness, and wills to fill it with light.

And this side is the eye of compassion. All the shadows are fled away, and the face is full of quiet light. This is a patient eye, a listening eye; it has all the time you need. That’s a good thing, because this process of healing will take a long time, probably all your remaining time on earth.

And this side is the eye of compassion. All the shadows are fled away, and the face is full of quiet light. This is a patient eye, a listening eye; it has all the time you need. That’s a good thing, because this process of healing will take a long time, probably all your remaining time on earth.

Picture the face of a clock, as if it represented the flow of history. At noon, let’s place a time that was very friendly to Christians, say the 1950s. At the bottom of the dial, at 6:00, let’s put a time when Christians suffered for their faith, like the days of the early martyrs.

Picture the face of a clock, as if it represented the flow of history. At noon, let’s place a time that was very friendly to Christians, say the 1950s. At the bottom of the dial, at 6:00, let’s put a time when Christians suffered for their faith, like the days of the early martyrs.

So the fifties are at noon, the Roman persecution at 6:00, and where are we now? Are we at 9:00, or 3:00? Are we rising or falling? I don’t know.

But which was actually the bad time? Christians suffered terribly in the early persecutions, but they also rose to great heights. Their lives radiated the light of Christ, and, even powerless and suffering, they drew many to the faith. We are still moved to the heart by their stories.

On the other hand, the fifties saw a lot of perfunctory, bland Christianity. It was easy to be a Christian and not mean much by it. This was hard on those who felt Christ challenge them to a holy and humble life. And the fifties couldn’t have been such a perfect time to raise your kids; look what happened when those same kids hit the sixties.

History will continue to roll around and around that dial. But at all times God is at the center. He is always fully present to every Christian of every age, not even a whisper away. Whether we face our culture’s approval or disdain, God has placed us in the time that he thinks we are able to bear.

The early Christians didn’t have the power to do anything in the public square except die. But they did that with such grace that they drew the whole world to Christ. If we follow in their footsteps, we cannot go far wrong.