[Clean Monday, March 14, 2016]

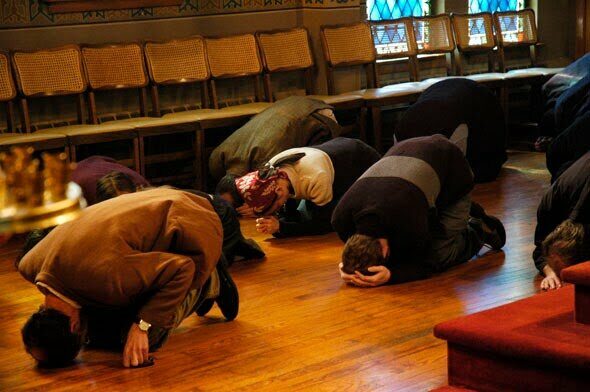

During Lent we make more prostrations. That’s a process that begins by making the sign of the Cross, then bowing down, resting your knees on the floor and then touching your forehead to the floor. I’ve collected, below, some photos of people making prostrations from around the internet.

It’s a prayer posture that we often see in the Old Testament, when we read that people “fell on their faces.” (I don’t know if prostrations are ever used in Judaism any more.) Here’s a detail of the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser, (827 BC, now in the British Museum), which depicts the Jewish King Jehu (2 Kings 9-10) making a prostration before the conqueror Shalmaneser III of Assyria.

What prostrating most looks like to Western people is Muslim worship; Muslims carried it over from their earlier history as Orthodox Christians, just as Christians continued the practice from their Jewish roots. When Orthodox make prostrations, we don’t do them as neatly as Muslims do, all in a row, and men and women worship together.

(A point of confusion can be that the term “prostrate” or “prostration” in English literaly means lying flat on the floor. In Western liturgical practice, if a prostration is called for, that’s what is meant. In the East the term got applied instead to this act of “falling on your faces.”)

People might do prostrations all together during a service, or privately, apart from liturgical worship. If you visited a holy site, you might feel like expressing your awe and gratitude with a prostration. Some people make prostrations when they say the Jesus Prayer, during their private prayer time. When you ask someone to forgive you, it is beautiful (though not required) to accompany the request with a prostration. It represents your recognizing the presence of Christ in the person you have offended.

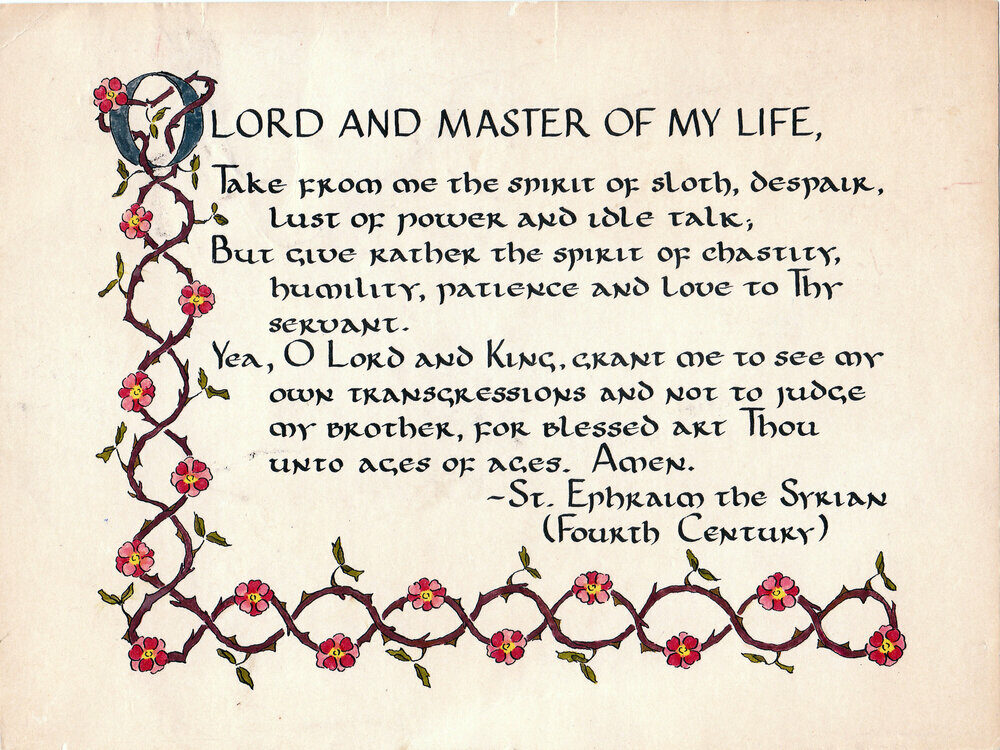

There is a prayer we say frequently in Lent, and accompany with prostrations. It is the Prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian (AD 306-373):

We make a prostration at the end of each line, so three in all. It’s not a uniform process, and some do it more quickly, others more slowly. Some can’t make a prostration very well (or maybe they can get down easily enough, but have trouble getting back up!), and instead make a “metania,” making the sign of the Cross and then bowing and reaching to the floor with the right hand. It’s not like everyone is *required* to make a prostration; it’s meant instead to help you express your sorrow for sin with your whole body, not just your words, and your gratitude for forgiveness.

How-to: Begin by making the sign of the Cross. Begin bending forward, and begin to lower the palms of your hands to rest on the floor. It’s more efficient to focus on what you do with your hands that what you do with your knees, because if you focus on knees, it tends to become an awkward 2-stage camel-like process. But if you instead follow the sign of the cross with a gentle controlled-fall forward, aiming to rest your palms to the floor, and allowing your knees to fall into place—then you can push off lightly from your palms and return to a standing position.

It’s a way the Judeo-Christian tradition has expressed awe, documented back to 827 BC (and remember all those who “fell on their faces” from Genesis to Revelation). Why not give it a try?

The descendants of the Levites make a prostration during the Yom Kippur service, but I think that is the only time liturgically.

FMG: Thanks.

In Orthodox Judaism all males in most communities prostrate during the Yom Kippurim and Rosh Hashana services, regardless of whether they are Levitical or not.

The Rambamists and some non-denominational Rabbinical independents prostrate in all their prayers, year round.

Both males and females in Qaraite Judaism and Scriptural independents prostrate year round in all their prayers.