I use these images when I give the talk, “An Overview of Icons.” There’s more content in the talk, of course, but there are some notes with each image.

1. The baptistry from the church at Dura Europas, Syria, from about 245 AD.

1 a. Neighboring synagogue with similar frescos. Moses rescued in the river.

1 b. Another image from the Dura Europas synagogue. Jewish worshippers saw frescoes with biblical scenes, as in Orthodox churches today.

1 c. The Good Shepherd, symbolizing Christ, San Callisto Catacombs in Rome; early 200’s.

1 d. Three Young Men in the fiery furnace

1 e. Daniel in the lion’s den. Ouspensky: viewer “provided with an internal attitude which he had to preserve at all times.”

1 f. Third century, a woman praying with hands lifted (the “orans” or “standing” position) —perhaps the Theotokos?

1 g. The Virgin nursing her Child, while a philosopher (Balaam?) points to a star. Catacomb of Priscilla, c. 250.

1 h. The Palatine Graffitti, 200-250. “Alexamenos worships his god.”

2 a. Christ in a mosaic floor of a home in Hinton, near London, perhaps 300.

2 b. A view of the entire floor; Christ is in the center of the larger room. Now in the British Museum in London.

3. Mosaic of the Transfiguration, in the apse above that altar at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai, c. 550. Kurt Weitzman, Jan 1964 National Geographic: “…hanging like a veil.”

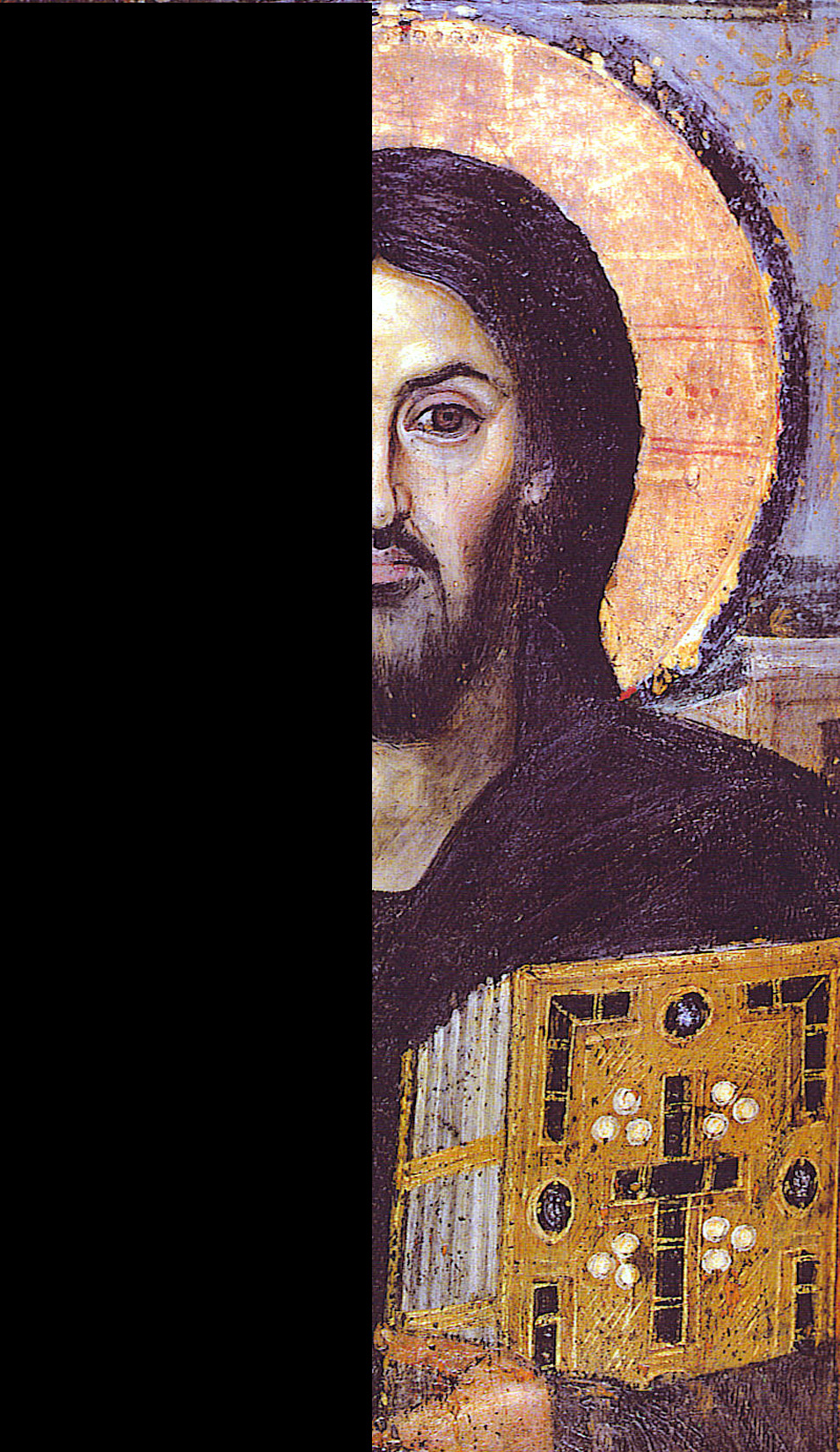

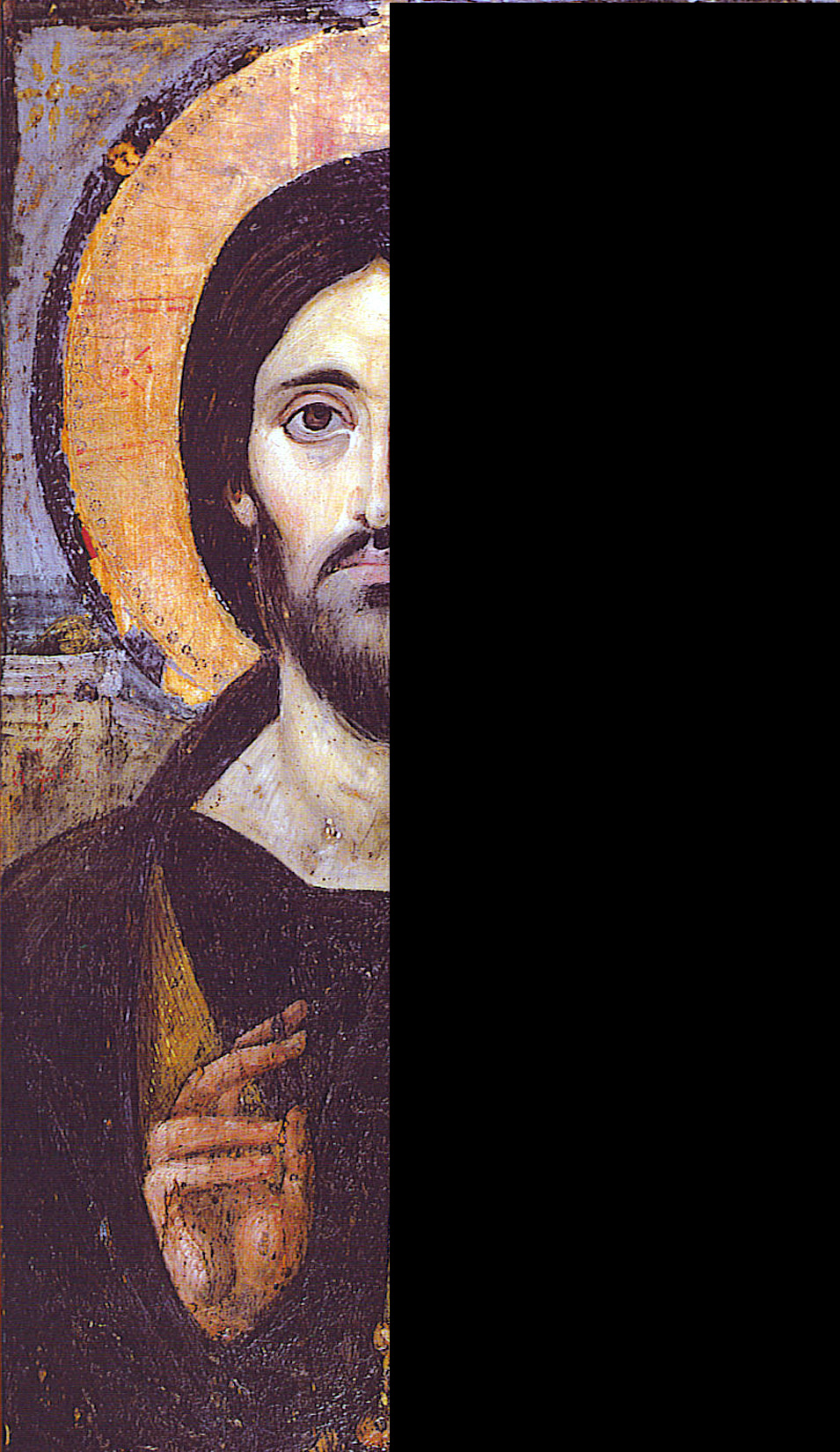

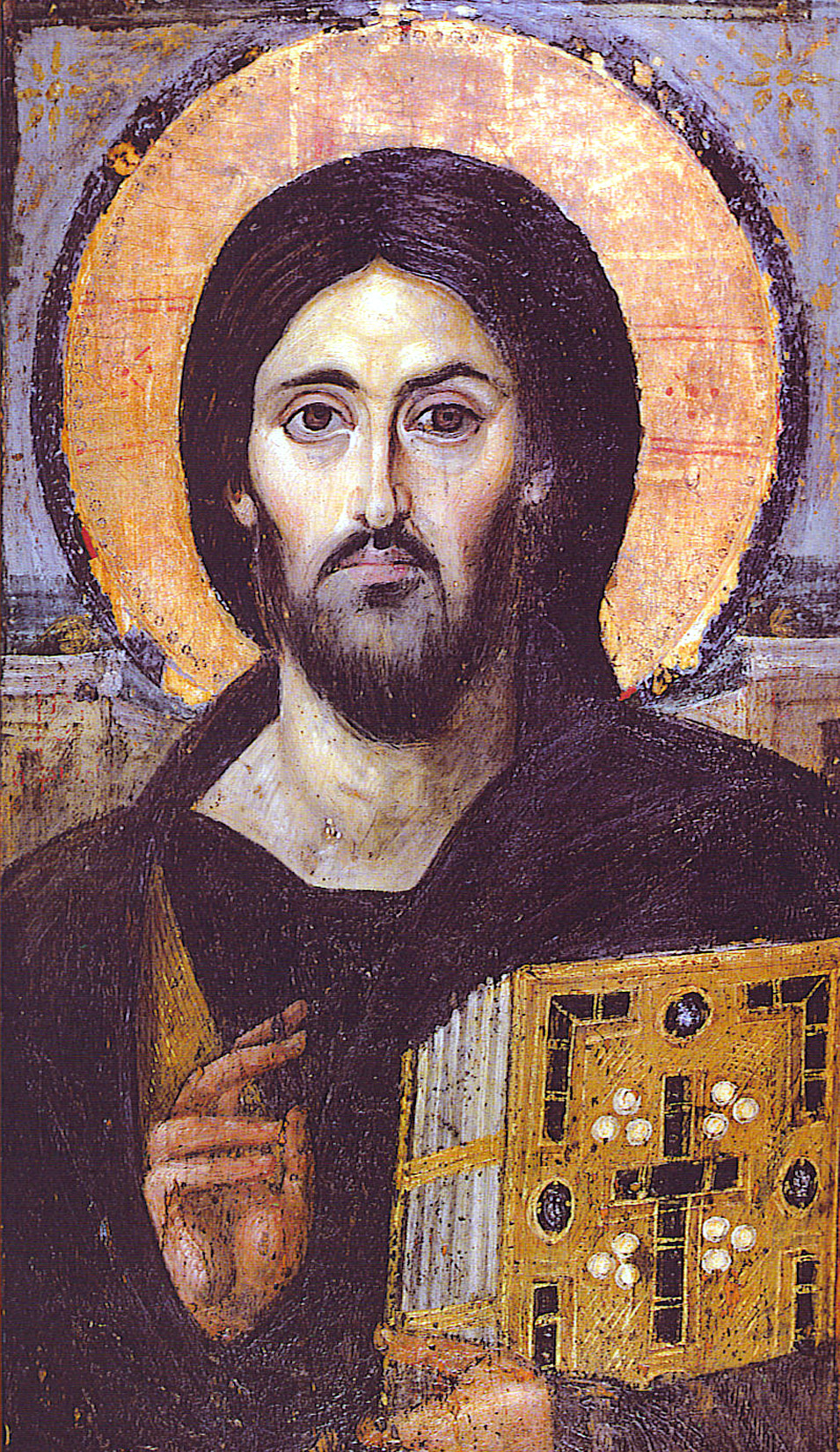

4. Christ of Sinai, a wax encaustic icon, c. 550, has been at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt Sinai since its founding.

4 a. The right side of the icon.

4 b. The left side of the icon.

4 c. Now you see how the two sides go together.

4 d. The Christ of Sinai strongly resembles the portraits made of people who had died. These were painted (wax encaustic) on wooden panels. Here are three such portraits. They are associated with Fayum in Egypt, though it was a Greek custom; they have just been preserved best in Egypt. This young man has the large, expressive eyes typical of these portraits.

4 e. A young woman looking very lifelike and beautiful.

4 f. The image was attached to the shrouded body of the deceased, held in place above the face with the strips of cloth.

5. The Christ of Sinai is number one among the top three “greatest hits” of the world’s favorite icons.

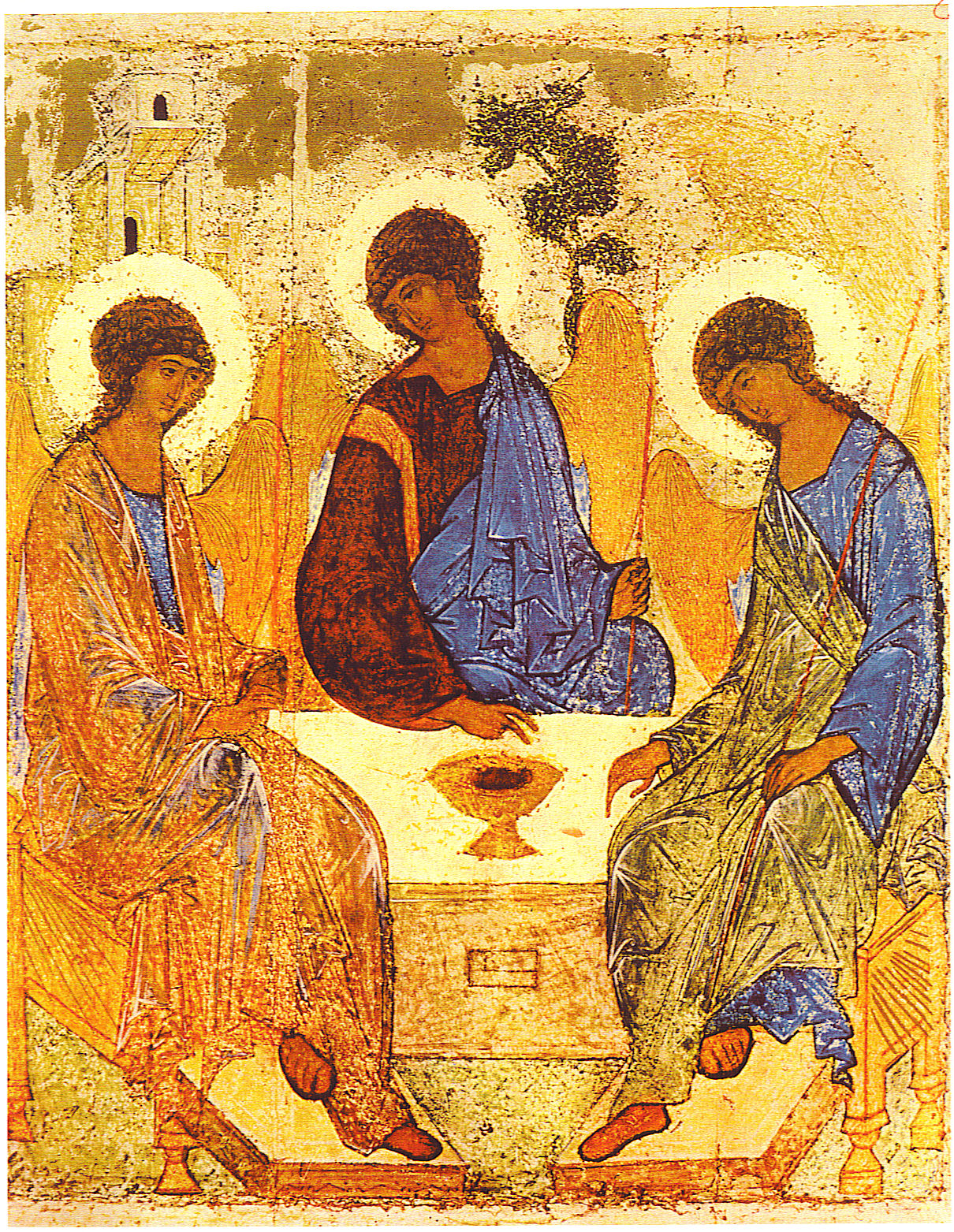

6. Number two could be the “Old Testament Trinity” of St. Andrei Rublev, painted c. 1420.

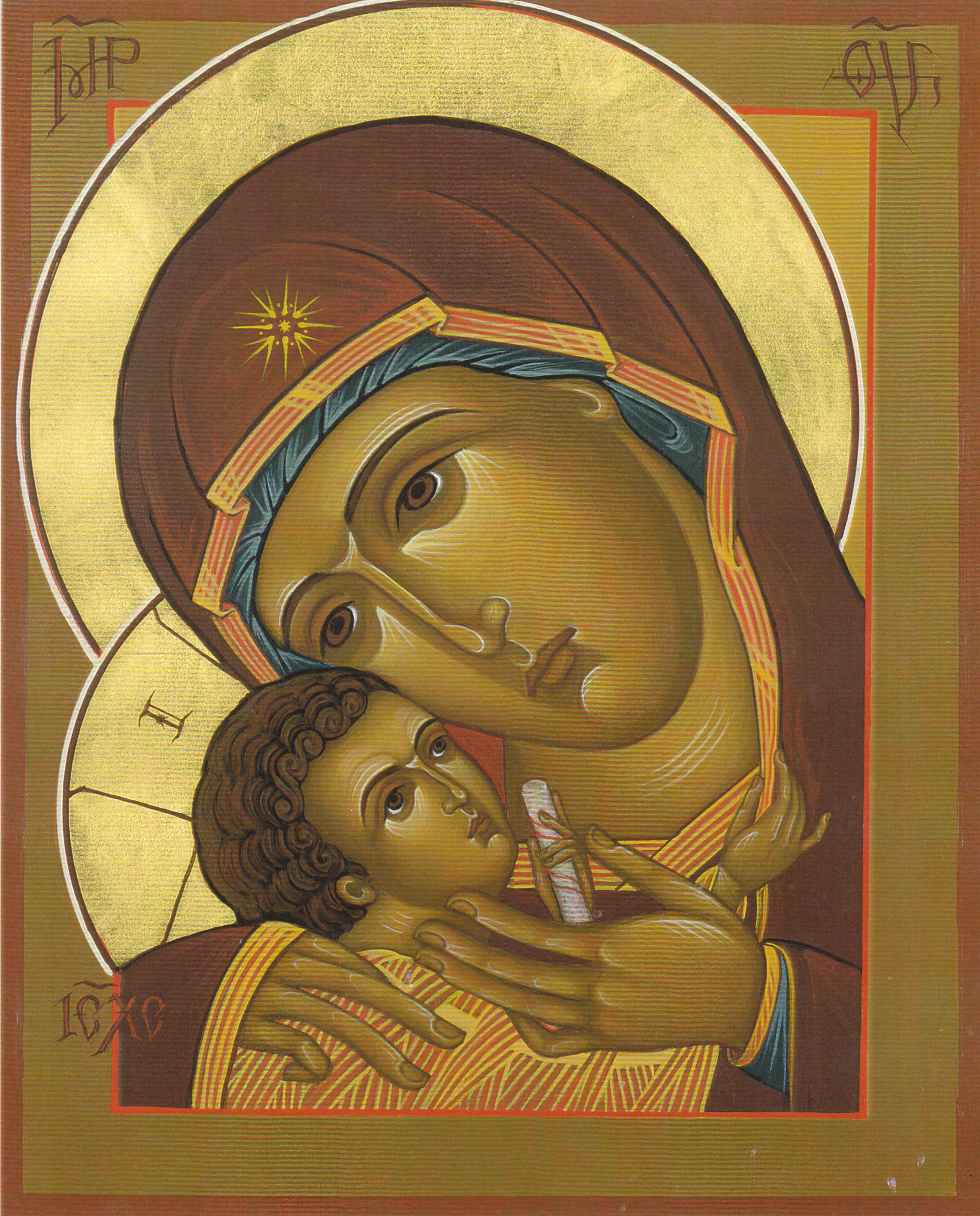

7. Number three could be the Virgin of Vladimir, which appears in history in 1131.

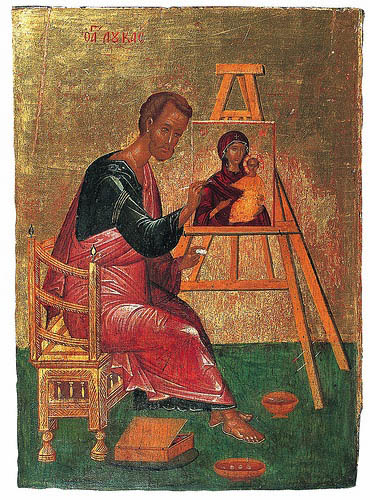

7 a. Some say this image was painted by St. Luke the Evangelist, when he went to interview Mary for his Gospel.

7 b. Here are three views of the “Madonna and Child” over 1800 years. First, the image from the Catacombs of Priscilla, c. 250.

7 c. And here again is the Virgin of Vladimir. There are three ways of depicting the Virgin, and one like this, where she and her Son are embracing closely, is called “Tenderness” or “Glykophilousa” (which means sweet-kissing).

7 d. And this is an icon by the iconographer Robin Armstrong, of Alaska, painted in 2000. The image remains the same.

8. The second way of depicting the Virgin and Child is one in which the Son sits upright on her lap, and she gestures toward him. This is called “Directress” or “She who shows the way” (“Hodigetria” in Greek).

8 a. This large icon has two sides; it was designed to be carried in processions. The Theotokos’ expression is gripping.

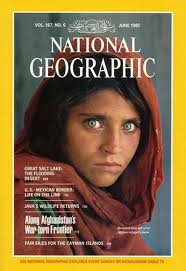

8 b. It reminded me of this Afghani woman from the cover of National Geographic some years ago:

8 c. The image on the other side of the Theotokos was this one, the “King of Glory.”

9. The third way the Theotokos can be depicted is the “Virgin of the Sign,” Isaiah 7:14. This one is from Kiev, c. 1200.

9 a. The Virgin of the Sign recalls the catacomb image of a woman praying in the orans position:

9 b. However the Virgin of the Sign shows us the unborn Christ Child in her womb, like this image from the 4th century:

9 c. If a church has an icon of the Virgin of the Sign, it is usually in the apse, above the altar.

10. Here is a new icon, depicting the meeting of the Virgin and Elizabeth, when St. John the Forerunner recognized his Lord in the womb.

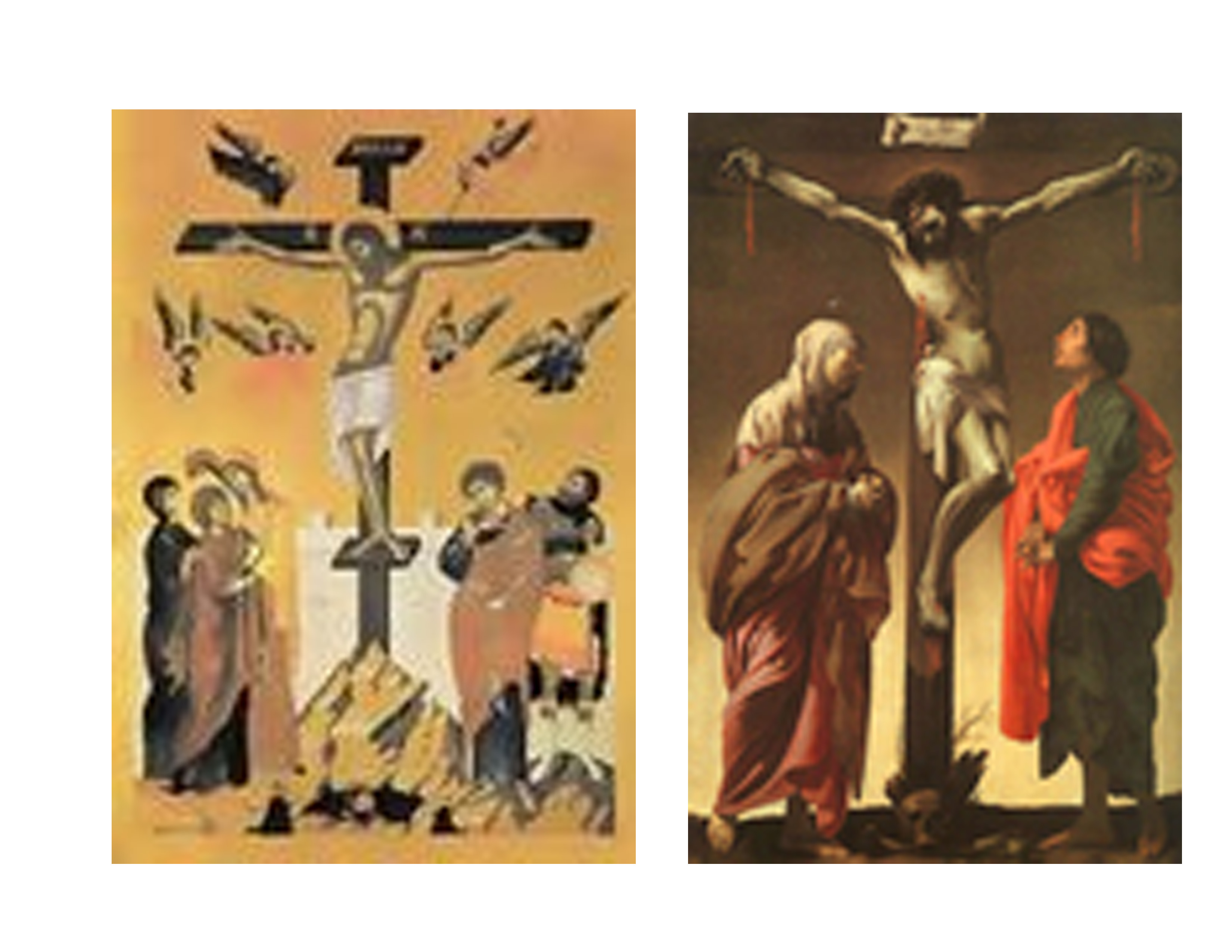

11. When “The Passion of the Christ” came out, I became interested in why Western Christian art, since the middle ages, has tended to present Christ’s sufferings in a graphic and bloody way, while Eastern Christian art has continued the early tradition of discreet and respectful treatment, as if we turn our eyes away. Both these images come from the early 1600s.

12. This 1320 icon from the church of Chora, outside Constantinople, depicts the “rescue” view of the atonement, as Christ defeats death and raises Adam and Eve.

13 a. Sometimes Christians are driven out of a place, and the new conquerors deface the icons. This crucifixion, from Goreme, was painted in the 10th century.

13 b. They particularly would scratch out the eyes; the eyes frightened them. Another icon from Goreme, in the 11th century.

13 c. This one is from Kolossi in the 15th c. With all the rejection and mockery our Lord suffered, it still goes on.

14. Finally, how are icons used in worship? They are companions in prayer.