[Newsday, March 7, 2004]

“Were you there when they crucified my Lord?” asks the old Gospel hymn.

Mel Gibson’s powerful film, “The Passion of the Christ,” has brought many viewers “there,” and I rejoice with those who say it deepened their faith. I can understand why this film moves them so much.

But I don’t think they understand why a fellow-believer might prefer a different approach. It seems to them that any less-than-graphic portrayal is weak – “sanitized.”

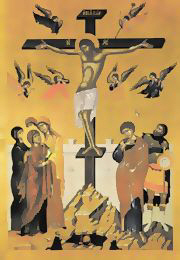

But is that the only way to see it? Here, for example, are two paintings made early in the 17th century. The one with the golden background represents the Eastern Christian tradition, and is by the iconographer Emmanuel Lambardos of Crete. The other, emblematic of Mel Gibson’s Western tradition, is by the Dutch painter Hendrickter Brugghen.

The ter Brugghen Christ sags like a corpse, and he is corpse-colored, yellow and gray. Blood spills from his hands and side in streams of muted red. His face is bent in shadow, but his straining arms, bloated abdomen and perfectly articulated knee catch the metallic light.

If you look at the knees of Lambardos’ Christ you see two little circles. This painting doesn’t even attempt realism. Christ’s long, thin arms are open as if in offering. He stands on the foot platform weary but unbroken. His face is folded in sorrow, yet tranquil, and a spot of rose lingers on his cheek. All around him angels reel in awe.

The ter Brugghen is a better painting. Or is it? It’s more “realistic,” but that presumes that “reality” is what a news camera would capture. The icon tradition of the Christian East flavors images with deliberate “unreality” in order to preserve the inexpressible: manipulated perspective, geometric landscapes, golden backgrounds.

These two approaches represent different answers to the question, What does Christ’s suffering mean?

In medieval Europe, the idea arose that God could not simply forgive our sins; there had to be a payment. Christ paid this debt on the Cross. Others objected that Christ’s sufferings were not a payment but an example of love for us to imitate. In either case, the Passion became crystallized as the moment of salvation, and we were called to identify with Christ’s suffering.

The Eastern Church, however, maintained an earlier understanding. Here, God the Father does not need payment, and Christ is much more than an example. Instead, our salvation involves a real change in our being, a rescue from a state of decay. Christ’s Incarnation permeated our common life to restore God’s intimate, immediate presence. His resurrection destroyed death, freeing us from the darkness and misery that enslave mankind. In this story, the Passion plays an extraordinary part, but it is not the sole decisive moment.

Christ lives, and we live in a continuing interior communion that will assimilate us with his light and transform us to be like him. We don’t dwell on the idea that he is like us; the energy is all going in the other direction. We would not presume to identify with him, as if we understand what he’s going through and figure he feels about it like we would.

Ter Brugghen presents Christ’s gray body within arm’s reach, and John gazes at it in rapture. But in the icon the golden body is lifted high, reigning over heaven and earth. We cannot begin to understand what is transpiring here. Like the stricken angels, we cover our mouths.

The Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial in Washington is a wall of polished granite displaying thousands of names. But might someone say, in accord with the view of the Gibson film, that if we haven’t seen the suffering, we’re not taking it seriously enough? Let’s add a photo next to each name, showing the person at the moment of dying, blown apart or bleeding. Since we don’t have those photos, we’ll put look- alike actors in makeup, with latex wounds and fake blood. If we honor soldiers for dying, well then, let’s watch them die.

If your friend died in Vietnam, you would not want him treated that way. Why not give Jesus the same dignity?

Mel Gibson’s movie stands in a great tradition of Western art. But realistic depiction comes with a price. To turn a great sacrifice into specific images will inevitably reduce it. It turns it into an ordinary horrible act, the kind humans inflict on each other every day, pressed down to manageable size. As we fix the memory we cease to experience it. We turn it into something we can digest and explain.

But we cannot understand the Cross. If you were there, experiencing every moment with every sense, you still could not tell what transpired or how it swept through your soul.

Were you there? I don’t have a photo of what it was like. But as the old hymn says, “Sometimes it causes me to tremble.”